A recent JAMA article examined how risky being a surgeon in the U.S. is in terms of mortality compared to other professions. Using 2023 death records for people aged 25 to 74, which included both occupation and cause of death, the researchers compared surgeons with three groups: other physicians who are not surgeons, professionals with similar education and income levels, such as lawyers, engineers, and scientists, and the general working population. [1] (Note: this data is from a single year, so it doesn’t tell us the trend over time)

Key Findings:

Higher death rates for surgeons vs. nonsurgeon doctors

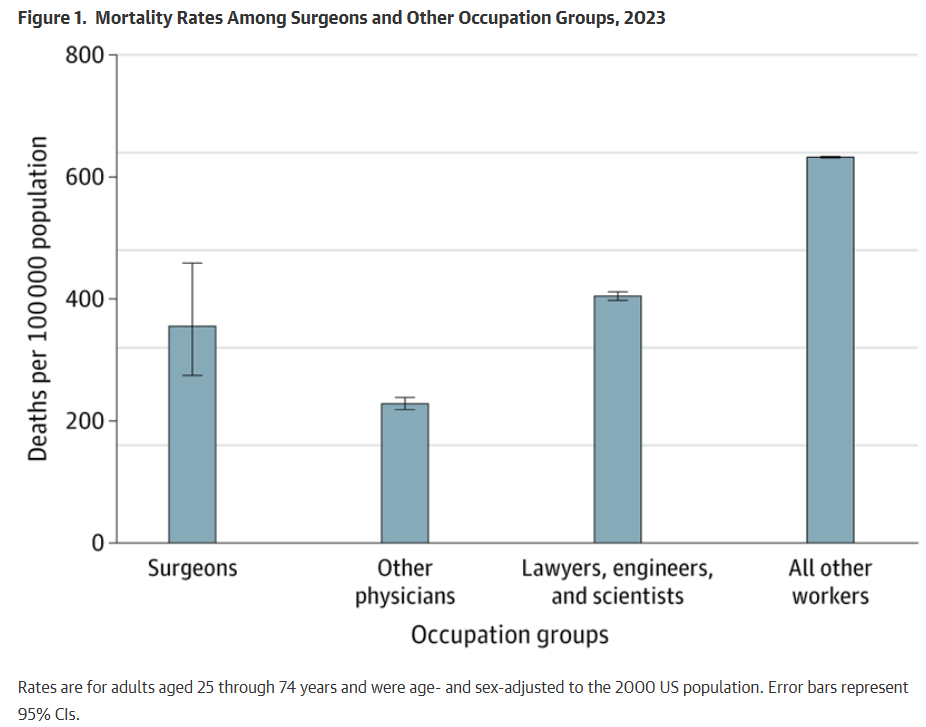

Surgeons have a higher mortality rate compared to nonsurgeon physicians, even after adjusting for age and sex. Specifically, the data showed about 355 deaths per 100,000 people among surgeons, compared with roughly 228 deaths per 100,000 among other physicians. This translates to a rate ratio of 1.56, meaning surgeons faced about a 56% higher risk of death than their nonsurgical peers. [1]

Compared to other professionals and general population

Surgeons’ mortality rates are similar to those of other highly educated professionals, such as lawyers, engineers, and scientists. However, surgeons fare better than the general working population overall, with a lower risk of death compared to the average worker. [1]

What people are dying of [1]

- For everyone (surgeons, physicians, etc.), the top causes are cancers (neoplasms) and heart disease. Surgeons have more deaths from certain causes than other groups.

- Particularly, surgeons had especially high death rates from cancer compared to even other physicians (about more than double).

- They also had higher ranks of death from motor vehicle crashes, high blood pressure (hypertension), and assault compared with other professions. For example, car crashes were one of their top 5 causes of death, more so than in many other occupations.

What this suggests

The higher risk faced by surgeons compared to other doctors may stem from the nature of their work rather than a lack of medical knowledge. Factors such as long hours, fatigue, stressful commutes or travel, exposure to workplace hazards like radiation or chemicals, and overall stress levels could all play a role. [1]

- Burnout rates among surgeons are high. Roughly 30%-38% in some studies show high levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, or feeling a low sense of achievement. Younger surgeons and women tend to be at higher risk. [2] Rates of burnout are estimated at 50–60% in orthopedics, higher than general surgery, and suicide risk among physicians is stark—40% higher in male doctors and 130% higher in female doctors compared to the general population. [6] Burnout doesn’t only hurt the surgeon’s quality of life. It’s linked with poorer patient care (errors, worse relationships with patients, possibly adverse outcomes), mental health problems (depression, anxiety), relationship issues (divorce, family strain), substance abuse, early retirement, and even suicide risk. Burnout among surgeons matters on several levels. For the surgeons themselves, it reduces quality of life and well-being and can lead to serious personal harm. For patients and health systems, burnout increases the risk of mistakes, compromises patient safety, and contributes to turnover or early retirement, all of which create instability and added costs. At the hospital or departmental level, burned-out surgeons are less productive, more likely to cut back their workload or leave altogether, and place additional strain on colleagues and resources [2]

- Healthcare workers who put in excessively long hours face dramatically higher risks of burnout. A study found that longer working hours are strongly linked to higher burnout among healthcare workers, with risk doubling past 60 hours a week, tripling past 74, and quadrupling past 84. Sleep loss played a major role in this connection; improving rest could prevent up to 73% of work-hour–related burnout in doctors and up to 29% in nurses. Nurses showed the highest burnout rates, while physicians worked the longest hours but were especially affected by poor sleep. Overall, the findings highlight that long hours and inadequate sleep are key drivers of burnout. [3]

- Workplace violence is a disturbing reality in surgical hospital wards, where healthcare staff face frequent physical assaults, verbal abuse, and even gender-based harassment from patients and visitors. In this Swedish study, interviews with nurses, assistant nurses, and a physician revealed that such violence—ranging from hitting and biting to threats and sexual harassment—is common yet often dismissed as “part of the job.” Staff reported that hospitals lacked proper systems, training, or clear guidelines to prevent or manage these incidents, leaving them anxious, unsupported, and at times reluctant to work. The ripple effects extended to patient care, as aggressive individuals often consumed more attention while others received less, raising broader safety concerns. The authors stress that violence is not limited to emergency departments and call for stronger prevention strategies, structured action plans, and better institutional support to protect both staff and patients.[4]

- Surgeons face frequent occupational exposures in the operating room. Orthopedic surgeons face significant workplace hazards backed by striking data.

- Nearly 99% of surgical residents experience a needlestick injury during training, with more than half going unreported; such injuries carry up to a 0.3% risk of HIV, 1.8% for Hepatitis C, and 6–30% for Hepatitis B. [5]

- Protective gear like N95s helps against infections but brings side effects. 37% of health workers reported headaches from use, and during COVID, this rose to 81%, while respirator CO₂ levels sometimes reached 3–4%, far above the 0.5% NIOSH safety limit. [5]

- Surgical smoke, which is 85–95% water vapor and 5–15% hazardous particles, can be as harmful as smoking a pack of cigarettes from just one procedure, yet only 14% of ORs use smoke evacuation devices, and in one survey, none of 22 surgeons used filtration sleeves correctly. [5]

- Noise exposure is another danger: orthopedic tools generate 85–120 dB, with peaks as high as 145 dB—levels that cause hearing loss—while knee replacement surgeries average 80–85 dB with peaks around 104 dB; unsurprisingly, 50% of orthopedic staff show signs of noise-induced hearing damage, yet hearing protection remains uncommon. [5]

- Radiation exposure is another major hazard: orthopedic surgeons get five times more radiation than other hospital staff, and one study found 29% developed malignancies, compared to just 4% in controls; female orthopedic surgeons face an 85% higher cancer risk than the general population and a threefold increase in breast cancer. [6]

- About two-thirds of orthopedic surgeons suffer work-related injuries, with 31% requiring surgery themselves. [6]

The findings highlight potential areas for improvement, including stronger safety measures both inside and outside the hospital, implementing work-hour limits, addressing risky driving habits, managing stress more effectively, and reducing exposure to harmful materials. [1]

References:

[1] Patel VR, Stearns SA, Liu M, Tsai TC, Jena AB. Mortality Among Surgeons in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2025;160(9):1032–1034. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2025.2482

[2] Balch CM, Freischlag JA, Shanafelt TD. Stress and Burnout Among Surgeons: Understanding and Managing the Syndrome and Avoiding the Adverse Consequences. Arch Surg. 2009;144(4):371–376. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2008.575

[3] Lin, R., Lin, Y., Hsia, Y., & Kuo, C. (2021). Long working hours and burnout in health care workers: Non-linear dose-response relationship and the effect mediated by sleeping hours—A cross-sectional study. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12228

[4] Jakobsson, J., Axelsson, M., & Örmon, K. (2020). The Face of Workplace Violence: Experiences of healthcare professionals in surgical hospital wards. Nursing Research and Practice, 2020, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1854387

[5] Kugelman, D., Weppler, C. G., Warren, C. F., & Lajam, C. M. (2022b). Occupational hazards of orthopedic surgery exposures: infection, smoke, and noise. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 37(8), 1470–1473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2022.03.034

[6] C. Ryu, R. et. al. (2021). Are we putting ourselves in danger? Occupational hazards and job safety for orthopaedic surgeons. Journal of Orthopaedics, Volume 24(March–April 2021), 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2021.02.023

Leave a comment