A few weeks ago, I ran across an article by Tiger Buford bringing up the concern that lately, the use of “nano” in orthopedics has been a buzzword and is starting to lose its actual meaning. If all technology is using “nano” technology, what makes it different from the other “nano”s? Well, not all nano is created equal. And in some cases…it’s not even nano.

What does nano mean?

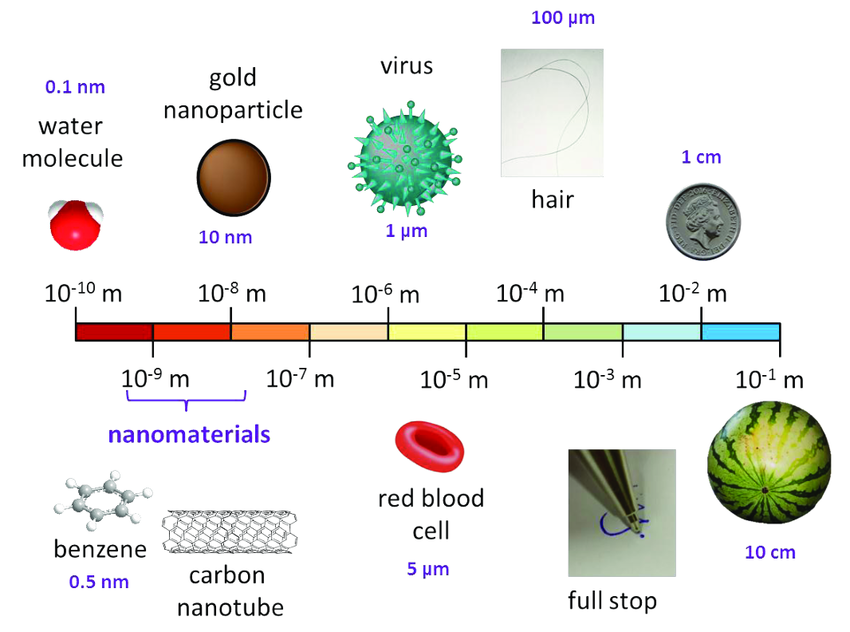

The term “nano” refers to objects or structures at the nanoscale, typically ranging between 1 and 100 nanometers (nm) in at least one dimension. At this scale, materials exhibit unique physical, chemical, and biological properties that differ from their bulk counterparts due to increased surface area, quantum effects, and enhanced interactions with biological systems.[1] Nanotechnology is defined as “the understanding and control of matter at dimensions between 1 and 100 nanometers, where unique phenomena enable novel applications” [2] While a nanomaterial is defined as “a material with any external dimension in the nanoscale or having internal structure or surface structure in the nanoscale” [3]

Applications in Orthopedics[4]

Nanotechnology in orthopedic surgery is advancing implant longevity, bone regeneration, infection prevention, and cartilage repair. Further research is needed to confirm long-term clinical safety, but nanomaterials have already demonstrated promising results in biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and infection control.

Nanotechnology has introduced numerous novel tools for orthopedic applications, including:

- Osteochondral defects, meniscus repair, and vertebral disks

- Targeted drug delivery for bone tumors

- Enhanced total joint replacements (TJRs) to prevent aseptic loosening

Nanotextured materials improve osteoblast adhesion and osteointegration, promoting better cell growth and tissue regeneration. Methods to reduce implant failures include:

- Nanostructured implant coatings, offering thermal insulation, corrosion resistance, and erosion protection

- Popular coating materials: Metalloceramics, hydroxyapatite, and nanostructured diamonds

Orthopedic Implants and Coatings

Nanostructured Implant Coatings

- Seven types of diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings significantly reduce abrasive wear in hip and knee implants.

- Nanostructured diamond (NSD & USND) coatings provide high adhesion to titanium but low adherence to cobalt-chrome and steel.

- Electrophoretic deposition is used to create the next generation of nanostructured hydroxyapatite coatings.

Anti-Cancer Properties of Nano-Implants

- Nano-selenium implants inhibit cancerous osteoblasts while promoting bone adhesion, calcium deposition, and alkaline phosphatase activity.

- Nanostructured magnesium alloy implants exhibit anti-tumor properties, reducing osteosarcoma cell adhesion.

Strengthening Implant Longevity

- Severe plastic deformation (SPD) enhances titanium’s biocompatibility and mechanical properties by reducing grain size to the nanoscale.

- Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) implants are being reinforced with carbon nanotubes for better durability.

Nanotechnology in Bone Cement

- Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) is commonly used but has short-lived antibiotic properties.

- Nanotechnology-based carriers (lipid nanoparticles, silica, and clay nanotubes) enable controlled drug release in bone cement.

- Nanostructured additives to PMMA enhance osteoblast activity and osseointegration.

- Modified nanoscale zirconia and barium sulfate particles improve biocompatibility and reduce implant failure rates.

Nanotechnology in Regenerative Medicine

Cartilage Repair (Chondrogenesis)

- Nanofibrous scaffolds made of polycaprolactone and gelatin show improved articular cartilage repair.

- A pilot study with 28 patients found 70% cartilage defect filling after 2 years.

- A 3-year clinical trial showed mixed results, requiring further research.

Tendon Healing

- Hydrosol nanoparticles for controlled mitomycin-C release reduce post-surgical adhesions.

- Nanocomposite scaffolds have been found to enhance collagen production and healing.

Bone Fracture Healing

- Nanofiber scaffolds enhance osteoblast migration and bone repair.

- Nano silicates in collagen-based hydrogels improve bone stiffness, porosity, and mineralization.

- Artificial bone grafts with nanostructures are being tested to replace traditional allografts.

Nanotechnology in Orthopedic Infections

- Orthopedic infections cause implant failures, requiring revision surgeries.

- Silver nano-coatings on implants significantly reduce bacterial colonization.

- IL-12 nanocoatings are being tested to prevent infections in open fractures.

- Vancomycin-loaded nano-delivery systems allow 100-hour controlled antibiotic release.

Nanocoatings and Implant Performance

- Nanocontoured surfaces improve osteoblast adhesion and reduce implant failure.

- Surface roughness modifications increase protein adsorption and cell integration.

- Calcium and phosphate coatings enhance osseointegration.

Bone Replacement Materials

- NanOss™ (Hydroxyapatite nanocrystals): Stronger than stainless steel, mimicking natural bone.

- VITOSS® (β-tricalcium phosphate nanoparticles): High porosity and vascular penetration, improving bone graft performance.

- Bone cement with nanoclay fillers improves mechanical properties.

Bone Grafting Innovations

- Nanomodified titanium alloy implants: Increased bone-to-implant contact and integration.

- Experimental studies with nano-modified bone grafts show enhanced osteoblast activity.

- Nano bone grafting techniques are still in preclinical stages but show promise.

What does NOT constitute as being “nano”?

Some technologies and materials are labeled as “nanotechnology” for marketing purposes or due to PARTIAL nanoscale features but do not meet the strict definition of nanomaterials (1-100 nm in at least one dimension).

Microstructure Implant Surfaces

Microroughened titanium surfaces are commonly used in orthopedic implants, including titanium joint replacements, to enhance osseointegration by improving bone attachment. These surfaces exhibit roughness within the micron range (1-100 µm) rather than at the nanoscale. Despite being marketed as “nano-textured” or “nano-enhanced,” these modifications occur at the microscale, which is approximately 1,000 times larger than true nanoscale features. For instance, sandblasting and acid-etching (SA) processes are widely used to achieve moderately rough surfaces on dental implants, which have been shown to improve osseointegration. Similarly, plasma spraying techniques are utilized to deposit coatings that enhance the surface roughness of titanium implants, further promoting bone integration. These methods produce surface irregularities within the 1–100 µm range, enhancing bone-implant contact and mechanical stability. [5]

Examples in the market include:

Zimmer Biomet’s Trabecular Metal™ Technology

- Description: This technology uses a highly porous tantalum material designed to facilitate bone ingrowth and implant stability. The material is engineered to mimic the structure of cancellous bone, improving biological fixation.

- Nano Claim: Marketed as a highly porous, nanostructured metal that enhances biocompatibility and mechanical stability.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The porous structure and microroughness exist within the 20-100 µm range, making it microscale rather than nanoscale.

DePuy Synthes’ POROCOAT® Porous Coating

- Description: POROCOAT® features sintered bead technology, creating a microrough surface on titanium implants. The coating enhances biological fixation by providing a stable environment for bone integration.

- Nano Claim: Marketed as an “advanced porous nanotechnology” that promotes superior osseointegration.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The sintered beads result in roughness within the 50-100 µm range, placing them firmly in the microscale category rather than true nanotechnology.

Stryker’s Tritanium® Technology

- Description: Tritanium® is a highly porous titanium alloy designed to mimic the structure of cancellous bone. It is used in spinal and joint implants to promote bone ingrowth and long-term fixation.

- Nano Claim: Marketed as a “nano-engineered porous metal” that optimizes mechanical and biological performance.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The porous structure and microroughness fall within the 40-80 µm range, meaning its surface modification is at the microscale rather than nanoscale

Polyethylene Wear-Resistant Liners in Joint Replacements

Highly Cross-Linked Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) is widely used in hip and knee replacements due to its high wear resistance and durability. Some manufacturers market these implants as “nano-polyethylene” or “nano-enhanced” to suggest superior performance. However, the modifications in UHMWPE occur at the molecular or micrometer level, rather than at the true nanoscale (1-100 nm). Research by Kurtz et al. (2020) analyzed UHMWPE liners and found that, despite being labeled as “nanotechnology-based,” their structural and material enhancements take place at the micron and molecular levels, rather than incorporating true nanoscale modifications.[6]

Examples in the market include:

E1® Antioxidant Infused Technology by Zimmer Biomet:

- Description: This technology incorporates vitamin E into UHMWPE to enhance oxidative stability and wear resistance in joint implants.

- Nano Claim: Marketed as utilizing advanced nanotechnology to improve material properties.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The integration of vitamin E occurs at the molecular level, not within the true nanoscale range.

X3® Advanced Bearing Technology by Stryker:

- Description: A UHMWPE material subjected to a three-step, sequential irradiation and annealing process to enhance cross-linking and wear resistance.

- Nano Claim: Promoted as a “nano-treated” polyethylene to suggest superior performance.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The cross-linking process modifies the polymer at the molecular level, not at the nanoscale.

Durasul® Highly Cross-Linked Polyethylene by Smith & Nephew:

- Description: A highly cross-linked UHMWPE designed to reduce wear in hip and knee replacements.

- Nano Claim: Marketed with implications of nanotechnology enhancements.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The cross-linking modifications occur at the molecular level, not within the nanoscale range.

AOX™ Antioxidant Polyethylene by Exactech:

- Description: UHMWPE blended with an antioxidant (vitamin E) to improve oxidative stability and wear characteristics.

- Nano Claim: Presented as incorporating nanotechnology for enhanced performance.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The blending process operates at the molecular level, not at the nanoscale.

Nano-Hydroxyapatite Coatings with Agglomerated Particles

Hydroxyapatite (HA) coatings on titanium implants are widely used to promote osseointegration by mimicking the composition of natural bone mineral. Some of these coatings are marketed as “nano-HA” due to the presence of hydroxyapatite particles at the nanoscale. However, in many cases, these individual nanoparticles tend to agglomerate, forming larger micron-scale structures. As a result, while the raw material may include nanoscale particles, the final coating itself does not remain at the true nanoscale (1-100 nm), but rather falls into the microscale range. A study titled “Biocompatibility Studies on a Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Biomaterial” observed that HA appeared as larger agglomerated particles both inside and on the lamellar surface of collagen. The addition of the inorganic phase resulted in a decrease in the volume of macropores within the collagen matrix, and smaller pores, only a few microns (1.6-1.9 µm) in size, were also observed. [7] Another study, “Electrodeposited Hydroxyapatite-Based Biocoatings: Recent Advances and Future Directions,” highlighted that the hydroxyapatite coatings require controlled surface roughness/porosity, adequate corrosion resistance, and favorable tribological behavior. The deposition rate must be sufficiently fast, and the coating technique needs to be applicable at different scales on substrates with diverse structures, compositions, sizes, and shapes.[8]

Examples in the market include:

Promimic’s HA^{nano} Surface®

- Description: Promimic offers the HA^{nano} Surface®, a surface modification technology designed to enhance osseointegration by combining high wettability, optimal surface chemistry, and nano-roughness. This modification aims to mediate bioactivity and specific protein adsorption to the implant, thereby regulating cell behavior and influencing tissue regeneration.

- Nano Claim: The product is marketed as a nano-thin surface that enables newly formed bone to grow directly into the micrometer topography of the implant surface, providing mechanical stability.

- Actual Scale of Modification: While the surface incorporates nano-sized hydroxyapatite particles, these particles can agglomerate, resulting in micro-scale structures. The company notes that with the particle-based HA^{nano} Surface, there is no risk of cracking or delamination of the implant.

Hiossen’s ETIII NH Implant

- Description: Hiossen’s ETIII NH Implant features a nano-hydroxyapatite coating intended to accelerate the healing process, enhance hydrophilicity, increase bone formation (Bone Implant Contact – BIC), and improve the quality of newly formed bone (Bone Area Fraction Occupancy – BAFO), while maintaining the original implant microtopography. [9]

- Nano Claim: The implant is promoted as having a nano-coated hydroxyapatite surface that improves osseointegration, particularly under early loading conditions in the posterior maxilla. [10]

- Actual Scale of Modification: Although the coating consists of nano-sized hydroxyapatite particles, studies indicate that these particles tend to agglomerate, forming larger micro-scale structures. This agglomeration can affect the uniformity and effectiveness of the nano-coating. [10]

Additively Manufactured 3D Porous Implants with Nano-HA Coating

- Description: Research has explored the development of additively manufactured three-dimensional porous implants coated with nano-hydroxyapatite to improve bone ingrowth and initial fixation. These implants aim to combine the benefits of 3D printing with nano-scale surface modifications to enhance osseointegration.[11]

- Nano Claim: The implants are described as having a nano-hydroxyapatite coating that enhances bone ingrowth and initial fixation, leveraging the properties of nano-scale hydroxyapatite to improve implant performance. [11]

- Actual Scale of Modification: Despite the use of nano-hydroxyapatite particles, there is a tendency for these particles to agglomerate, leading to micro-scale surface features. This agglomeration can influence the overall effectiveness of the nano-coating in promoting osseointegration.

Nanostructured Magnesium Alloys That Are Actually Micro-Grained

Magnesium-based orthopedic implants are often marketed as “nanostructured” due to their purported enhanced mechanical properties and biocompatibility. However, many of these so-called “nano-magnesium” implants actually possess grain sizes in the micro-range, classifying them as microcrystalline rather than nanocrystalline. For example, a study by Sun et al. (2022) investigated a nanostructured Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy processed via high-pressure torsion (HPT). The research revealed that while the alloy initially achieved an average grain size of approximately 50 nm, annealing at temperatures of 623 K and 673 K resulted in grain growth to about 350 nm and 500 nm, respectively. This indicates that despite initial nanostructuring, the grains coarsened to the microscale upon thermal exposure, challenging the “nano” classification of such implants.[12]

Examples in the market include:

AZ91 Magnesium Alloy with Nanocomposite Coating

- Description: The AZ91 magnesium alloy, when coated with a nanocomposite layer, is designed to enhance corrosion resistance and biocompatibility for orthopedic applications. [13]

- Nano Claim: The coating is referred to as a “nanocomposite,” suggesting that it incorporates nanoscale features to improve performance.

- Actual Scale of Modification: Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed that the composite nanoparticles within the coating have an average size of 50 ± 20 nm, confirming their nanoscale nature. [14]

AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Subjected to Severe Shot Peening (SSP)

- Description: The AZ31 magnesium alloy underwent Severe Shot Peening (SSP), a surface treatment intended to induce grain refinement and enhance mechanical properties. [15]

- Nano Claim: SSP is reported to produce nanostructured surface layers, implying grain sizes reduced to the nanometer scale.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The SSP process resulted in the formation of nanocrystalline surface layers with grain sizes in the nanometer range, as confirmed by microscopy analyses.

Drug-Eluting Bone Cements with “Nano” Drug Carriers

Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bone cements are commonly used in orthopedic surgeries to anchor implants and fill bone defects. To prevent post-operative infections, these cements often incorporate antibiotics. Some formulations are marketed as “nano-enhanced” due to the inclusion of nanoparticles designed to deliver antimicrobial agents. However, while these drug carriers, such as lipid nanoparticles, silica, and clay nanotubes, may be nanoscale, the bulk cement structure remains unchanged. Additionally, the actual size of these “nano-drug carriers” can vary, and their effectiveness depends on their ability to release antibiotics over extended periods. For instance, lipid nanoparticles, nano-silica, and clay nanotubes have been added to standard bone cement (PMMA) to enhance drug delivery, providing prolonged antimicrobial activity. [16]

Examples in the market include:

PMMA Bone Cement with Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs)

- Description: Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement integrated with mesoporous silica nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin (DOX) aims to provide localized chemotherapy drug delivery, particularly for reconstructing defects post-surgical resection of spinal metastases. [17]

- Nano Claim: The incorporation of MSNs is intended to facilitate targeted drug delivery, leveraging the nanoparticles’ high surface area and porosity for sustained DOX release.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The MSNs utilized have a size range of approximately 100–150 nm, confirming their nanoscale dimensions. However, the bulk PMMA cement matrix remains unchanged at the macroscopic level.

Composite Bone Cement with Natural Micro/Nanoscale Additives

- Description: A commercial bone cement (Simplex P) preloaded with vancomycin is modified by adding natural materials such as halloysite nanotubes (HNTs), nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC), micro-fibrillated cellulose (MFC), and nano-fibrillated cellulose (NFC) to enhance drug elution and mechanical properties. [18]

- Nano Claim: The use of nanomaterials like NFC and NCC is intended to improve antibiotic release profiles and mechanical strength due to their high surface area and interaction with the polymer matrix.

- Actual Scale of Modification: The additives vary in size: NCC particles are typically less than 100 nm in length, qualifying as nanoscale, while MFC and NFC have larger, micron-scale fiber lengths. Despite the nanoscale size of some additives, the overall structure of the bone cement remains at the macroscopic level. [18]

Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) Coatings in Orthopedic Implants

Diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings are utilized in orthopedic implants, such as hip and knee prostheses, to reduce wear and friction. Some manufacturers market these coatings as “nanostructured” due to the arrangement of carbon atoms at the nanoscale. However, the overall thickness of these coatings typically ranges from hundreds of nanometers to several micrometers, classifying them as thin films rather than true nanotechnology. For instance, studies have reported DLC coatings with thicknesses of 300 nm, 500 nm, and 650 nm, which exceed the nanoscale threshold of 100 nm. [19]

Examples in the market include:

Medthin™ 40 Series by Ionbond

- Description: The Medthin™ 40 series comprises DLC coatings designed for medical applications, including orthopedic implants. These coatings provide excellent protection against abrasion, tribo-oxidation, and adhesive wear, making them suitable for coating medical instruments, tools, and implants. [20]

- Nano Claim: Ionbond refers to these as “DLC coatings,” highlighting their diamond-like properties but does not explicitly label them as “nanostructured.”

- Actual Scale of Modification: The specific thickness of the Medthin™ 40 series coatings is not detailed in the provided information. However, DLC coatings are typically within the micrometer range, often between 2 to 5 micrometers, which is above the nanoscale threshold. [20]

Micronite Coatings by Micromy

- Description: Micromy offers a surface layer called “micronite,” which is a type of DLC coating with outstanding tribological and corrosive properties. These coatings are approved for medical use under the guidelines of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), making them suitable for sensitive applications like implants. [21]

- Nano Claim: The term “micronite” suggests a focus on micron-scale properties, and there is no explicit claim of nanostructuring.

- Actual Scale of Modification: As the name implies, “micronite” coatings are designed at the micron scale, indicating that their structural modifications occur within the micrometer range, not at the nanoscale.

References:

Article that inspired this post — Tiger. (2025, February 15). Fake nano and real nano in orthopedics –. https://orthostreams.com/2025/02/fake-nano-and-real-nano-in-orthopedics/

[1] Joudeh, N., & Linke, D. (2022). Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists. Journal of Nanobiotechnology, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01477-8

[2] About Nanotechnology. (n.d.). National Nanotechnology Initiative. Retrieved March 17, 2025, from https://www.nano.gov/about-nanotechnology#:~:text=Nanotechnology%20is%20the%20understanding%20and%20control%20of,nanometers%2C%20where%20unique%20phenomena%20enable%20novel%20applications.

[3] Nanotechnologies — Plain language explanation of selected terms from the ISO/IEC 80004 series. (n.d.). In ISO Online Browsing Platform (OBP) (ISO/TR 18401:2017(en)). International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved March 17, 2025, from https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:tr:18401:ed-1:v1:en

[4] Abaszadeh, F., Ashoub, M. H., Khajouie, G., & Amiri, M. (2023). Nanotechnology development in surgical applications: recent trends and developments. European Journal of Medical Research, 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01429-4

[5] Schupbach, P., Glauser, R., & Bauer, S. (2019). Al2O3 Particles on Titanium Dental Implant Systems following Sandblasting and Acid-Etching Process. International Journal of Biomaterials, 2019, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6318429

[6] The UHMWPE Handbook. (2004). Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=bkuFjppEdMcC&lpg=PP1&ots=pphc2dUBC6&dq=Kurtz%20et%20al.%20(2020)%20analyzed%20UHMWPE%20liners&lr&pg=PR12#v=onepage&q&f=false

[7] Filip Ionescu, O. L., Mocanu, A. G., Neacşu, I. A., Ciocîlteu, M. V., Rău, G., & Neamţu, J. (2022). Biocompatibility Studies on a Collagen-Hydroxyapatite Biomaterial. Current health sciences journal, 48(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.12865/CHSJ.48.02.12

[8] Safavi, M. S., Walsh, F. C., Surmeneva, M. A., Surmenev, R. A., & Khalil-Allafi, J. (2021). Electrodeposited Hydroxyapatite-Based Biocoatings: Recent Progress and Future Challenges. Coatings, 11(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11010110

[9] Mela, O. A., Tawfik, M. A., Ahmed, W. M. a. S., & Abdel-Rahman, F. H. (2022). Efficacy of nano-hydroxyapatite coating on osseointegration of early loaded dental implants. International Journal of Health Sciences, 696–712. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6ns2.4998

[10] Amin, O. A., Shehata, I. M., Kamel, H. M., & Elbokle, N. N. (2024). Assessment of stability of early loaded nano coated hydroxyapatite implants in posterior maxilla. Journal of Nanotechnology and Nanomaterials, 5(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.33696/nanotechnol.5.049

[11] Watanabe, R., Takahashi, H., Matsugaki, A., Uemukai, T., Kogai, Y., Imagama, T., Yukata, K., Nakano, T., & Sakai, T. (2022). Novel nano‐hydroxyapatite coating of additively manufactured three‐dimensional porous implants improves bone ingrowth and initial fixation. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B Applied Biomaterials, 111(2), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.35165

[12] Wanting Sun, Yang He, Xiaoguang Qiao, Xiaojun Zhao, Houwen Chen, Nong Gao, Marco J. Starink, Mingyi Zheng. (2022). Exceptional thermal stability and enhanced hardness in a nanostructured Mg-Gd-Y-Zn-Zr alloy processed by high pressure torsion. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/468330/2/1_W_Sun_Journal_of_Magnesium_and_Alloys.pdf

[13] Razavi, M., Fathi, M., Savabi, O., Vashaee, D., & Tayebi, L. (2014). In vivo study of nanostructured akermanite/PEO coating on biodegradable magnesium alloy for biomedical applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 103(5), 1798–1808. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.35324

[14] Razavi, M., Fathi, M., Savabi, O., Tayebi, L., & Vashaee, D. (2020). Biodegradable Magnesium Bone Implants Coated with a Novel Bioceramic Nanocomposite. Materials, 13(6), 1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13061315

[15] Bagherifard, S., Hickey, D. J., Fintová, S., Pastorek, F., Fernandez-Pariente, I., Bandini, M., Webster, T. J., & Guagliano, M. (2017). Effects of nanofeatures induced by severe shot peening (SSP) on mechanical, corrosion and cytocompatibility properties of magnesium alloy AZ31. Acta Biomaterialia, 66, 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.11.032

[16] Indelli, P. F., Ghirardelli, S., Iannotti, F., Indelli, A. M., & Pipino, G. (2021). Nanotechnology as an Anti-Infection Strategy in Periprosthetic Joint Infections (PJI). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 6(2), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6020091

[17] Garakani, M. M., Cooke, M. E., Weber, M. H., & Rosenzweig, D. H. (2024). Nanoparticle-functionalized acrylic bone cement for local therapeutic delivery to spine metastases. Exploration of BioMat-X, 1(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.37349/ebmx.2024.00010

[18] Cherednichenko, K., Sayfutdinova, A., Rimashevskiy, D., Malik, B., Panchenko, A., Kopitsyna, M., Ragnaev, S., Vinokurov, V., Voronin, D., & Kopitsyn, D. (2023). Composite Bone Cements with Enhanced Drug Elution. Polymers, 15(18), 3757. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15183757

[19] Zia, Abdul Wasy & Balakrishnan, G. & Lee, Seunghun & Kim, J.-K & Kim, Tae & Song, Jungll. (2015). Thickness dependent properties of diamond-like carbon coatings by filtered cathodic vacuum arc deposition. Surface Engineering. 31. 85-89. 10.1179/1743294414Y.0000000254.

[20] Ionbond IHI Group. (2025, January 21). DLC coating | Diamond-Like Carbon | IHI Ionbond. https://www.ionbond.com/en-us/technology/dlc/

[21] Wikipedia contributors. (2022, August 21). Micromy. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Micromy

IMAGE – https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Nanotechnology-and-Nanoscale-science_fig1_359787620

Leave a comment