I have been in spine for over 10 years and it’s very easy to forget that while we are busy showing the benefit from implant to implant, there are actual reasons why the instrumentation is being used and why fast fusion is important, specifically speaking for spinal interbody fusion. This can be translated over to other anatomy in the spine, but interbody fusion is my bread and butter, so that’s where I’m coming from.

The rate at which fusion occurs in interbody fusion procedures is crucial for several reasons:

Restoration of Spinal Stability:

Delayed spinal fusion can prolong instability, potentially leading to persistent symptoms and necessitating additional interventions. Persistent instability may result in ongoing pain and functional limitations, often requiring further surgical procedures to achieve the desired spinal stability and symptom relief.[1,2,3]

Reduction of Non-Union Risk:

Accelerated fusion decreases the likelihood of non-union (pseudarthrosis), a condition where the intended fusion fails to solidify. Non-union can result in continued pain and may necessitate revision surgery.[4]

Approximately 1.36 million instrumented spinal fusion procedures were conducted in 2021, with projections estimating 1.50 million in 2023 and 1.52 million in 2024.[5] Non-union rates for one-level lumbar interbody fusion range from 5% – 10%. [6,7,8,9,10] Non-union rates for one-level cervical range from 7% cranial levels to 21% caudal level.[11] On average, 176,776 fusions will fail per year due to non-unions.

Non-union, for failed spinal fusion, pseudoarthrosis, occurs when vertebrae do not heal and fuse after surgery, leading to persistent pain and instability. The causes of non-unions can include patient-related factors (like age, smoking, diabetes, malnourished, and obesity) and surgical factors (inadequate stabilization, poor bone quality, and infection).[12,13] In all cases, there is an impairment to the bone healing process.

Prevention of Hardware Complications:

Timely fusion minimizes the duration that spinal implants bear mechanical loads. Prolonged reliance on hardware due to delayed fusion can lead to implant fatigue, loosening, or failure, compromising surgical outcomes.[14]

Spinal fusion instrumentation is primarily used to enhance spinal stability, correct malalignment, and promote bone fusion, particularly in cases where instability or deformity exists. Metal rods, screws, and cages act as structural supports, immobilizing the vertebrae to allow bone grafts to fuse. Hardware assists in realigning the spine by holding vertebrae in proper positions during the healing process. Immobilization prevents micromotion, which is critical for effective bone graft incorporation and long-term fusion.[15] In all cases, the hardware is present to maintain a form of stability until the body can heal and fuse. The hardware is meant to supplement fusion, not be the end-all, be-all solution, and the sooner the spine can fuse, the sooner the patient is not dependent on the spinal hardware, which has the potential to loosen, fracture, or cause other complications.[16]

Facilitation of Rehabilitation:

Early fusion allows patients to engage in rehabilitation programs sooner, promoting mobility and enhancing overall recovery. Delayed fusion may restrict rehabilitation efforts, potentially leading to muscle atrophy and reduced functional outcomes.[17]

Early mobilization is a proven, effective strategy for reducing complications, shortening hospital stays, and improving overall recovery in spinal surgery patients. Early mobilization protocols (day of surgery or shortly thereafter) significantly reduce perioperative complications, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), pneumonia, and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Implementing early mobilization consistently decreases hospital stays, reducing overall healthcare costs and freeing up resources. Pre-habilitation and postoperative rehabilitation improve functional outcomes and patient satisfaction without increasing complication rates.[18]

Economic Considerations:

Prompt fusion can reduce healthcare costs by decreasing the need for prolonged postoperative care, additional imaging studies, and potential revision surgeries associated with delayed or failed fusion.[19]

[1] Ivel. (n.d.). Understanding spinal fusion failure: causes, symptoms, and treatments. Long Island Neuroscience Specialists. https://longislandneuro.com/spinal-fusion-failure/

[2] Schultz, J. R., MD. (2024, November 13). Is pain after spinal fusion normal? All you need to know. Centeno-Schultz Clinic. https://centenoschultz.com/spinal-fusion-complications-years-later/

[3] Rosenstein. (2023, December 4). Recognizing the red flags: What are the symptoms of a failed lumbar fusion? – North Texas Neuro Surgery. North Texas Neuro Surgery. https://ntneurosurgery.com/2023/11/22/what-are-the-symptoms-of-a-failed-lumbar-fusion/

[4] Osc, O. (2023b, June 21). Non-union of spinal bones in fusion Surgery: Part I – Causes. Orthopaedic and Spine Center of Newport News. https://www.osc-ortho.com/blog/non-union-of-spinal-bones-in-fusion-surgery-part-i-causes/

[5] Research, I. (2023b, October 5). How Many Spinal Fusions are Performed Each Year in the United States? iData Research. https://idataresearch.com/how-many-instrumented-spinal-fusions-are-performed-each-year-in-the-united-states/

[6] Manzur, M., Virk, S. S., Jivanelli, B., Vaishnav, A. S., McAnany, S. J., Albert, T. J., Iyer, S., Gang, C. H., & Qureshi, S. (2019). The rate of fusion for stand-alone anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review. The Spine Journal, 19(7), 1294–1301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.03.001

[7] Manzur, M. K., Steinhaus, M. E., Virk, S. S., Jivanelli, B., Vaishnav, A. S., McAnany, S. J., Albert, T. J., Iyer, S., Gang, C. H., & Qureshi, S. A. (2020). Fusion rate for stand-alone lateral lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review. The Spine Journal, 20(11), 1816–1825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2020.06.006

[8] Malham, G. M., Ellis, N. J., Parker, R. M., & Seex, K. A. (2012). Clinical Outcome and Fusion Rates after the First 30 Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusions. The Scientific World JOURNAL, 2012, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/246989

[9] Wu, R. H., Fraser, J. F., & Härtl, R. (2010). Minimal access versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine, 35(26), 2273–2281. https://doi.org/10.1097/brs.0b013e3181cd42cc

[10] Meng, B., Bunch, J., Burton, D., & Wang, J. (2020). Lumbar interbody fusion: recent advances in surgical techniques and bone healing strategies. European Spine Journal, 30(1), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06596-0

[11] Jang, H. J., Kim, K. H., Park, J. Y., Kim, K. S., Cho, Y. E., & Chin, D. K. (2022). Endplate-specific fusion rate 1 year after surgery for two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion(ACDF). Acta Neurochirurgica, 164(12), 3173–3180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05377-6

[12] Osc, O. (2023, June 21). Non-union of spinal bones in fusion Surgery: Part I – Causes. Orthopaedic and Spine Center of Newport News. https://www.osc-ortho.com/blog/non-union-of-spinal-bones-in-fusion-surgery-part-i-causes/

[13] Florida Spine Associates. (2024, November 25). What are the most common symptoms of pseudarthrosis. https://floridaspineassociates.com/2021/08/27/what-are-the-most-common-symptoms-of-pseudarthrosis/

[14] Sinicropi, S. (2015, June 10). Non-Union after Spine Fusion Surgery | Dr. Stefano Sinicropi. Dr. Stefano Sinicropi, M.D. https://sinicropispine.com/non-union-after-spine-fusion-surgery/

[15] Hanley, Jr., E.R. The indications for lumbar spinal fusion with and without instrumentation. (1995, December 15). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8747269/

[16] Young, P. M., Berquist, T. H., Bancroft, L. W., & Peterson, J. J. (2007). Complications of spinal instrumentation. Radiographics, 27(3), 775–789. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.273065055

[17] Ryu, W. H. A., Richards, D., Kerolus, M. G., Bakare, A. A., Khanna, R., Vuong, V. D., Deutsch, H., Fontes, R., O’Toole, J. E., Traynelis, V. C., & Fessler, R. G. (2021). Nonunion Rates After Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion: Comparison of Polyetheretherketone vs Structural Allograft Implants. Neurosurgery, 89(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyab079

[18] Epstein, N. (2014). A review article on the benefits of early mobilization following spinal surgery and other medical/surgical procedures. Surgical Neurology International, 5(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.130674

[19] Osc, O. (2023b, June 21). Non-union of spinal bones in Fusion Surgery: Part II – treatment. Orthopaedic and Spine Center of Newport News. https://www.osc-ortho.com/blog/non-union-of-spinal-bones-in-fusion-surgery-part-ii-treatment/

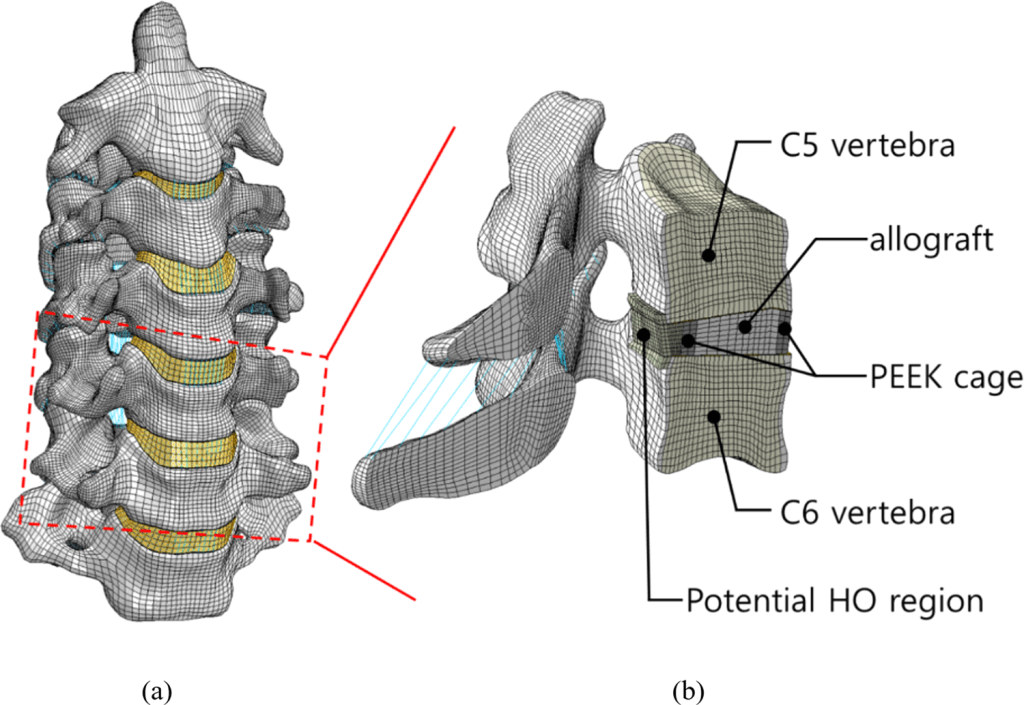

IMAGE – Park, W. M., & Jin, Y. J. (2019). Biomechanical investigation of extragraft bone formation influences on the operated motion segment after anterior cervical spinal discectomy and fusion. Scientific Reports, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54785-9

Leave a comment