The history of noncompete agreements goes back centuries, with the first documented case in 1414. In the beginning, English courts wouldn’t enforce them at all, seeing them as restrictions on free trade. This held true until 1621, when a key exception emerged. Agreements limited to a specific area became enforceable. Finally, in 1711, the case Mitchel v Reynolds cemented the modern approach. Now, courts analyze the specifics of each agreement to determine if it’s legally binding.[1]

For my almost 14 years in the medical device industry, I have had 3 non-competes, the first lasting 24 months (which is tough when you’re restricted from working in a field you literally went to college for). Then came the news of the FTC ban on non-competes, and I had to know more (along with a little celebrating).

Under the final Noncompete Rule [2]:

- All new noncompetes are banned*. The rule states that it is an unfair method of competition, a violation of Section 5, for employers to enter in to noncompetes with workers.

- For existing noncompetes, it’s a little different.

- For senior executives**, existing noncompetes can remain in force.

- With workers*** other than senior executives, noncompetes are not enforceable after the effective work.

* Any agreement that prevents someone from working for a competitor after leaving their current job is banned. This includes clauses that penalize someone for competing or make it financially difficult to do so. [3]

**“senior executive” refer to workers earning more than $151,164 who are in a “policy-making position.” [2]

*** it does not apply to entities over which the FTC traditionally lacks jurisdiction, nor does it apply to franchisee/franchisor contracts—although, as noted above, the definition of “worker” extends to employees working for a franchisee or franchisor. [3]

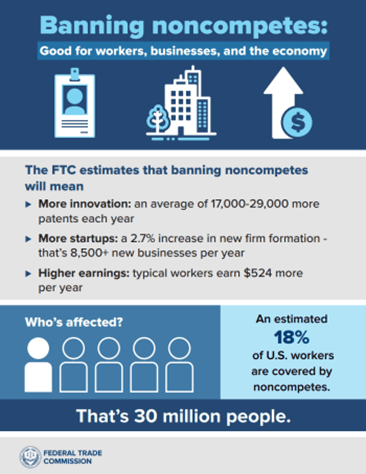

I found a fun little info graph summarizing what the FTC hopes to accomplish with this ban.

There will be a wait of at least 120 days after the rule is published before it starts being enforced. It could be even longer if there are legal challenges. [3] The final rule’s expected effective date is September 4, 2024. Once the rule is effective, market participants can report information on a suspected violation of the rule to the Bureau of Competition by emailing noncompete@ftc.gov. [2]

Non-compete agreements are used by employers to prevent workers from going to competitors, but their effects are debated.[4]

- Pros:

- Protecting confidential business information is the most common reason cited by employers for using NCAs.

- Cons:

- Stakeholders argue that lower-wage workers often lack access to confidential information.

- Workers may feel pressured to sign NCAs without negotiation due to limited job options or lack of awareness.

- Employers rarely enforce NCAs, but when they do, it applies to all worker types.

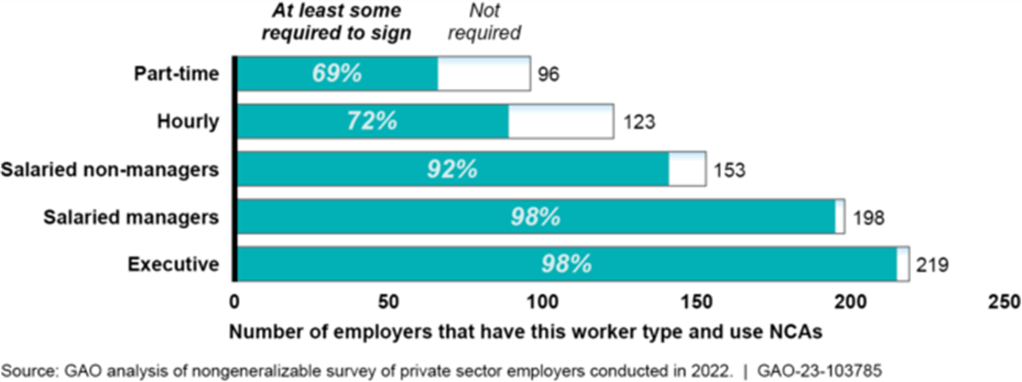

Noncompete Agreements (NCAs) by Worker Type, among Responding Employers Using NCAs [4]

References:

[1] Wikipedia contributors. (2024, May 1). Non-compete clause. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-compete_clause

[2] Noncompete rule. (2024, May 7). Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/rules/noncompete-rule

[3] Polk, D. (2024, April 25). The FTC non-compete rule. Davis Polk. https://www.davispolk.com/insights/client-update/ftc-non-compete-rule#:~:text=By%20its%20terms%2C%20the%20final%20rule%20will%20not%20come%20into,delayed%20further%20due%20to%20litigation.

[4] Noncompete Agreements: Use is Widespread to Protect Business’ Stated Interests, Restricts Job Mobility, and May Affect Wages. (2023, May 16). U.S. GAO. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-103785

Leave a comment